CUSWF Book Club Selections

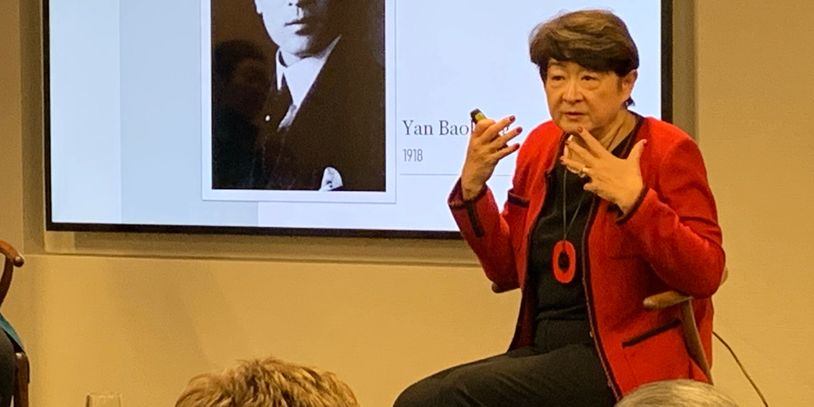

Lan Yan, author of The House of Yan

NEW YORK, January 29, 2020 -- At the China Institute, NYC, Lan Yan gave a riveting talk about her new memoir, The House of Yan, CUSWF's January Book Club Selection.

Lan Yan, an attorney and Vice Chairman and CEO, Lazard China, vividly describes the history of an era in China from the moving and difficult times in her life captured in her memoir, The House of Yan, published by Harper.

CUSWF Book Club - This Fish is Fowl: Essays of Being

A Conversation with author Xu Xi and author and filmmaker Ann Hedreen

We at CUSWF were so moved by Xu Xi's new book of essays This Fish is Fowl: Essays of Being, we wanted to share them with you as our latest CUSWF Book Club Selection.

We are delighted to have this exclusive conversation with Xu Xi by noted author, filmmaker and teacher Ann Hedreen.

“In the end, you write who you are, fish, fowl, mongrel, or whatever hybrid creature you happen to be, regardless of what supposedly equals ‘success’ for a writer,” asserts author Xu Xi in This Fish is Fowl/Essays of Being, published this year by the University of Nebraska Press in its acclaimed American Lives series. Xi’s book is a remarkable and timely addition to the series, which is edited by Tobias Wolff. Together, her sharply detailed essays give us a rich portrait of a life that is at once uniquely American (Xi is a naturalized citizen) and intricately global: Xi grew up in Hong Kong, the daughter of Chinese-Indonesian immigrants; her former corporate marketing career took her all over the world; and she now co-directs the Vermont College of Fine Arts’ International MFA program in creative writing.

From 2010 to 2018, Xu Xi lived primarily in Hong Kong, where she was the director of a new creative writing MFA program at City University of Hong Kong. She accepted the position and made the move so that she could live with and care for her mother through the late stages of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Following is a lightly edited version of my conversation with Xu Xi, which ranged from the ascendance of “World English” to how being her mother’s caregiver influenced her writing:

Tell me about the Vermont College of Fine Art’s International MFA in creative writing.

What we believe is that we need to embrace and understand the literature that’s in the English language from all over the world. Which means not just British and American, but the broader world of English language literature: Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Malaysian… and also so many people who have defected from their original language to write in English. China is very notable for that. We also have students from Thailand and Vietnam. (Continue reading)

About the authors

Xu Xi is Co-Director of The International MFA program in creative writing and literary translation at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is the author of This Fish is Fowl: Essays of Being (University of Nebraska Press/American Lives Series, 2019), Dear Hong Kong: An Elegy for a City, That Man in Our Lives, The Unwalled City and many other books.

Ann Hedreen is a writer, filmmaker and teacher. Her memoir, Her Beautiful Brain, won a 2016 Next Generation Indie award. Ann’s writing can also be found in 3rdAct Magazine and other publications. She has just finished a second memoir, The Observant Doubter.

A conversation with author Xu Xi and Ann Hedreen

The conversation with Xu Xi and author and filmmaker Ann Hedreen starts above.

Why was it important to you and fellow MFA co-director Evan Fallenberg (who lives in Tel Aviv) to emphasize the art of translation along with creative writing?

Because Evan is a translator and I read internationally—I read a lot of literature in translation—we felt that we’re not giving ourselves (as readers and writers) the benefit of the literature of the rest of the world if we don’t focus on translation.

What was it like to move into your parents’ Hong Kong flat after 40 years of frequently visiting, but never actually living there? (Xi lived and worked in Hong Kong earlier in her adult life, but had her own home.)

It was a big decision to have to actually move home. I was kind of shuttling back and forth (between Hong Kong and New York); my then partner and now husband and I, we’re used to shuttling. But I think for me the idea of actually really moving back, living there, taking a job, and the idea of going home to live—the idea that I would actually be in my mother’s home! …I started thinking about the suspending of life. Because life does sort of go into suspension, you know? This is not the thing you ever anticipated you would do… and I have no children, on top of that. If I had been a mother, I might’ve been better at this! But I was like, what? I’ve got to be a mom? How do I do this?! I’m turning 60, and I have to become a mother?!

The trouble with being a writer is your life is supposed to be so flexible, right? You can work anywhere? And I’m the eldest: that was a big part of it.

How is caregiving changing in China and Hong King?

Chinese society used to just naturally take in old people. Hong Kong society does not do that anymore. It’s not the way it was when I was a child. In China, they actually legislated at one point, to make people go home and visit their parents, after everybody came to work in the cities. So what does that tell you? This whole Confucian filial piety thing is not really the way the modern world operates. In China, when you travel so many miles from your village to Beijing or Shanghai or Chengdu to get a job, and whenever you go back home, your parents are wondering when are you going to have children and come home, and a lot of young people, they don’t want to come home.

What were some of the challenges you faced during your years of long-distance caregiving, when you were shuttling back and forth between Hong Kong, the U.S. and occasionally New Zealand?

You can only physically travel so much. It’s a long haul! I got really good at the long haul, but it’s not natural. (Although) sometimes, the travel itself becomes the reprieve.

How did the time you spent with your mom influence you as a writer?

(Before Alzheimer’s), my relationship with my mother was always very chatty. My family, we were a talking family. We discussed politics, family, why Auntie So-and-so is wearing what she’s wearing. And (as the illness progressed) it was very silent with my mother. And I came to actually appreciate that silence.

The silence was actually interesting for my writing. Because I wrote an incredible amount at the time I went home to live in Hong Kong. To the point where the book publishing became a little absurd; every year a new book was coming out… But it was partly because of being in Hong Kong at a time of great change. Culturally, we were going through so much change. And my mother didn’t want to leave Hong Kong. We tried to make her go to the U.S., and we gave up. And she never wanted to go back to Indonesia. Which I found very interesting. Even though (my parents) remained to the end very Indonesian, culturally. She didn’t know how to cook Chinese food until she came to Hong Kong!

I was trying to honor my mother’s wish to stay at home. And home for her really was this flat my family had lived in for almost 40 years in Hong Kong. But that wasn’t home for me, because I left Hong Kong a half a year after they moved there. So it was a curious thing to be in this home, my mother’s home, and I could imagine so much about her and her life in this apartment, and what about her past?

I wanted to write more. I would ask her questions, and she would change the answers, and then I realized: she lies without realizing she’s lying now. It made me think about narrative in a very different way. There’s so much about the way Alzheimer’s is that forces you to rethink linearity, narrative, memory. The idea of fiction and non-fiction becomes very interesting with an Alzheimer’s person.

Do you fear Alzheimer’s? I know I do.

I look for signs of it in myself. I actually started to set myself memory tests. I do fear it. I told my husband, if I get Alzheimer’s, just make sure you put me somewhere where I’m reasonably well taken care of, and do not take care of me at home. In Hong Kong, we could hire domestic help. We can’t afford to do that here.

I do think the big problem now is, there’s so much focus on: how do we cure this? How do we make it go away, take a pill? I think the focus should be: how do we help people who have Alzheimer’s live out their lives in a reasonably good way. As good as is possible. I think government and society should put money into elder care, training, more elder care facilities. I think that’s where better money would be spent in the near future. Obviously we need scientific research, we need to understand it. But we need to learn how to cope. If you want to keep someone at home, how do you do that? Or a facility, what should that look like?

What are you currently working on?

I’m writing shorter pieces, including an essay on the protests in Hong Kong. I’m also working on two novels. Both books deal with questions of memory. I think it’s probably a direct influence of dealing with my mother’s Alzheimer’s, and investigating in my own mind the question of what memory is.

Xu Xi is Co-Director of The International MFA program in creative writing and literary translation at the Vermont College of Fine Arts and author of This Fish is Fowl: Essays of Being (University of Nebraska Press/American Lives Series, 2019), Dear Hong Kong: An Elegy for a City, That Man in Our Lives, The Unwalled City and many other books.

Ann Hedreen is a writer, filmmaker and teacher. Her memoir, Her Beautiful Brain, won a 2016 Next Generation Indie award. Ann’s writing can also be found in 3rdAct Magazine and other publications. She has just finished a second memoir, The Observant Doubter.

CUSWF Book Club Selection: Women's Work

Join us in reading this thought-provoking and moving book!

On the surface, Megan Stack’s life was chaotic – reporting on war for the Los Angeles Times from more than a dozen countries, she was used to dropping everything and leaving in pursuit of a new story. The long hours on the road, the danger of traveling war-torn countries as a woman, and the heartbreaking conditions of those still living in the devastated countries were manageable to Stack – it wasn’t until she had her first child while living in China that she truly felt overwhelmed.

In WOMEN’S WORK: A Reckoning with Work and Home, by Megan K. Stack examines the very system which allowed her to keep working, and investigates the lives of her nannies, to see the cost of her own emancipation to the children who were left behind.

As Stack and her husband navigated growing professional and parental responsibilities, they continued to rely on nannies to bear the brunt of the household work. Stack could no longer ignore the reality that the progress on her book was only due to her exploitation of cheap labor, and she became increasingly aware of the desperate living conditions each of her nannies faced – domestic abuse, unexpected pregnancies, and medical crises. Domestic labor cannot be ignored – the intimacy of the household leaves no room for excuses of feigned ignorance. What she discovered is that the emancipation of upper-class women directly depends upon a permanent underclass of impoverished women, all desperate to provide for their own families.

WOMEN’S WORK is a deeply personal story, but it is also a probing and universal meditation on feminism, privilege, motherhood and the ethics that underpin our globalized societies.

“Women’s Work hit me where I live, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it. The discomfiting truths Stack reveals about caretaking and labor transcend cultural and national boundaries; this book is relevant to everyone, no matter how or where they live. Stack uses her reporting acumen to illuminate domestic workers’ struggles, but also fearlessly reveals the most vulnerable details of her own life in order to make her point. The masterfulness with which she tells these intertwined stories makes this book not just a work of brilliant journalism but a work of art.”

—Emily Gould, author And the Heart Says Whatever and Friendship

WOMEN’S WORK: A Reckoning with Work and Home by Megan K. Stack.

More CUSWF Book Club Selections!

Rediscover a Beloved Classic! Pearl S. Buck's The Good Earth

CUSWF partnered with the Pearl S. Buck International foundation and Chinese groups to read The Good Earth and analyse its meaning in light of changes in Chinese society. How is it still relevant? What makes the characters so moving? We will host events and talk to experts as we rediscover this Pulitzer Prize-winning novel and its author, Pearl S. Buck, winner of the Nobel Prize for literature for her body of work and humanitarian.

Our Book Club Selection for Work-Life Balance: Do Not Marry Before Age 30

Join us in reading Joy Chen's bestselling book Do Not Marry Before Age 30, which addresses a crucial issue in China today, the stigma of the “leftover woman.” Chinese women face extreme social pressure to marry by age 25 or be labeled "leftover." Women as young as 22 tell Joy they’re "leftover." The leftover-woman stigma is leading to serious problems today in China, including pressuring people to marry very young – resulting in exploding divorce rates - a well as resulting in a sense of sadness and isolation among so many wonderful, creative young Chinese women. Joy wrote her book for them, and for all the women of China.

CUSWF's Launches Our Bookclub!

We value the power of books and storytelling to help us shed light and understand the world a little better. So we are launching a bookclub.

Each month, we will feature books that we hope will be of special interest to you. We're starting with the publishing hit Crazy Rich Asians.

CUSWF and China Institute Celebrates The Good Earth

NEW YORK, February 13, 2019 -- CUSWF friends and members joined us for our first event with the China Institute as we hosted a reception and discussion of Ms. Buck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Good Earth, followed by a screening of the film inspired by the book.

Pearl S. Buck, a Nobel and Pulitzer-Prize-winning author, was an advocate for children and activist who spoke out against discrimination and injustice. Her humanitarian vision continues to be a source of inspiration today.

Two Things You Should Know About Crazy Rich Asians

Check out what Singaporean Dr. Rachel Yager wants you to know about Crazy Rich Asians.